Language is the Truest Form of Democracy

Language is the truest form of democracy. No one can completely control it. One of the things (and there are many) that makes “Nineteen Eighty-Four” so scary is the invention of Newspeak, eliminating words from the English language in order to limit thought. One of the more interesting aspects of that book is the appendix, which refers to Newspeak in the past tense. That seems to imply that Big Brother was not successful in completely controlling the language. I find that a reassuring thought.

Language is the truest form of democracy. No one can completely control it. One of the things (and there are many) that makes “Nineteen Eighty-Four” so scary is the invention of Newspeak, eliminating words from the English language in order to limit thought. One of the more interesting aspects of that book is the appendix, which refers to Newspeak in the past tense. That seems to imply that Big Brother was not successful in completely controlling the language. I find that a reassuring thought.

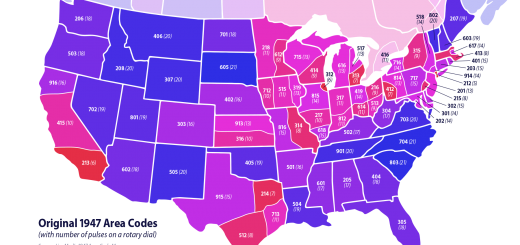

Place Names

Another aspect of the democratic nature of language is with place names. Like the Willis Tower in Chicago. Nobody calls it that. Likewise the Bernard F. Dickmann Bridge in St. Louis, since renamed the Congressman William L. Clay Sr. Bridge. It is, and will always be, the Poplar Street Bridge to me and millions of other St. Louisans. Even cities like Petrograd/Leningrad eventually reverted back to St. Petersburg. Now there are plenty of examples of name changes sticking as well, such as New York replacing New Amsterdam or Constantinople becoming Istanbul. But with these examples, there was a change in the demographic (Dutch to English and Greek to Turkish respectively), and the new demographic majority accepted these changes. And yet, the fact that these are such famous examples shows that the old names still remain there in the background, unforgotten.

Language Academies

Another example of this democratic process is with the language academies and other linguistic authorities. Some languages, like French, have established academies of language schools who regulate the language and decide what is and is not acceptable. They are only partially successful. In the case of the French Academy, they can make small tweaks to the spelling and style, and maybe guide the creation of new words, but there are also plenty of cases where a foreign word worked its way into the everyday speech despite their best efforts. For example, the academy says that email should be called “courrier electronique”, but most French speakers use the more concise English word. At the end of the day, some words stick and some don’t, and I don’t think that one individual, or even a concerted group of individuals, can completely stop the democratic tide.

Messy Etymologies

Sometimes new words appear even when they don’t make sense. For example, a about a decade or so ago, MP3 players were popular, with the most notable being Apple’s iPod. At the same time, people started using their iPods to listen to long-form “radio” programs on various topics, fittingly called Podcasts. Then the iPhone and other smart phones completely replaced iPods. Yet this type of media kept being called a Podcast. I remember the tech pundit Leo LePorte trying to popularize Netcast, which makes a lot more logical sense, but it didn’t stick. Years later, we find ourselves in the Golden Age of Podcasting, long after the iPod was a thing. I would imagine there are already younger and newer podcast fans out there who have no idea what an iPod is. The word has now completely deviated from its original etymology.

Language, like democracy, is a messy thing. And you know, I like it that way. Language doesn’t always make sense, but it works for getting the point across. And if and when it doesn’t work, people change it, without the control of a central authority. It just happens. Like life, language finds a way.

What do you think about the democratic aspect of language. Are there any local place names or words that you refuse to use despite a concerted change? Let me know your thoughts in the comment section.

At risk of sounding vacuous, I’d say we all avoid doing what we perceive as misusing language. What primarily varies is not a refusal to speak or write incorrectly, but rather our definitions of what we consider correct.

People sometimes move their correctness goalposts for unusual reasons, like a desire to fit in with certain people. I’ve seen people at work who misuse or mispronounce certain things solely because that’s how someone important says it and it would be faux pas (or too exhausting) to differ. This is like democracy in that while each person has his own vote, you can tell other people how to vote!