The Oddities of Area Codes

Area codes in the US seem pretty random. ZIP codes are organized somewhat by region, but area codes just seem to be made up of three arbitrary numbers. This is true nowadays, but there was originally a method to the madness. Area codes made a lot of sense for their time and place, though the system has been stretched significantly by changes in population and technology.

Before Area Codes

When telephones were first invented, they were connected in small local exchanges, with an operator manually connecting lines. This proved untenable for all but the smallest localities, and urban exchanges were soon automated. Automation worked fine for local numbers, but dialing long distance was a lot more difficult. The US was a hodgepodge of local exchanges. Thanks to Ma Bell’s monopoly, phone numbers were somewhat consistent, but there was still no national numbering system.

Real Time Dialing

Creating a national numbering system was harder than you might expect. Aside from building the infrastructure (not a small task), any national phone number plan would have to be compatible with existing phones. Unlike modern cell phones, landline phones have real time dialing. On a cell phone, you dial the whole number and press “send” to route the call. On a traditional phone, each number immediately routes the call through a different electrical circuit. So as soon as you dialed “286”, for example, you would be connected to the local exchange, with the machines there waiting for the remaining digits to connect you to your party. This meant that there was no easy way for the phone system to connect to long distance exchanges. If you wanted to call someone across the country, you had to go through the operator.

Letters and Numbers

Early phone numbers used letter mnemonics to make them easy to remember. Instead of 555-1212, you’d dial KLondike 5-1212, with the first two letters corresponding to a number on the dial. For each number from 2 through 9, there were three corresponding letters, 2=ABC, 3=DEF, etc. A side effect of this was that the first two digits of any local number were never 0 or 1. This meant there were no local exchanges with numbers like 214 or 802. As soon as you dialed that middle 0 or 1, the system would connect you to the long distance exchange, and route your call across the country. With this in mind, engineers at Ma Bell set about assigning area codes with the formula xyx, whereas x was a number from 2 through 9, and y was either 0 or 1.

The North American Numbering Plan

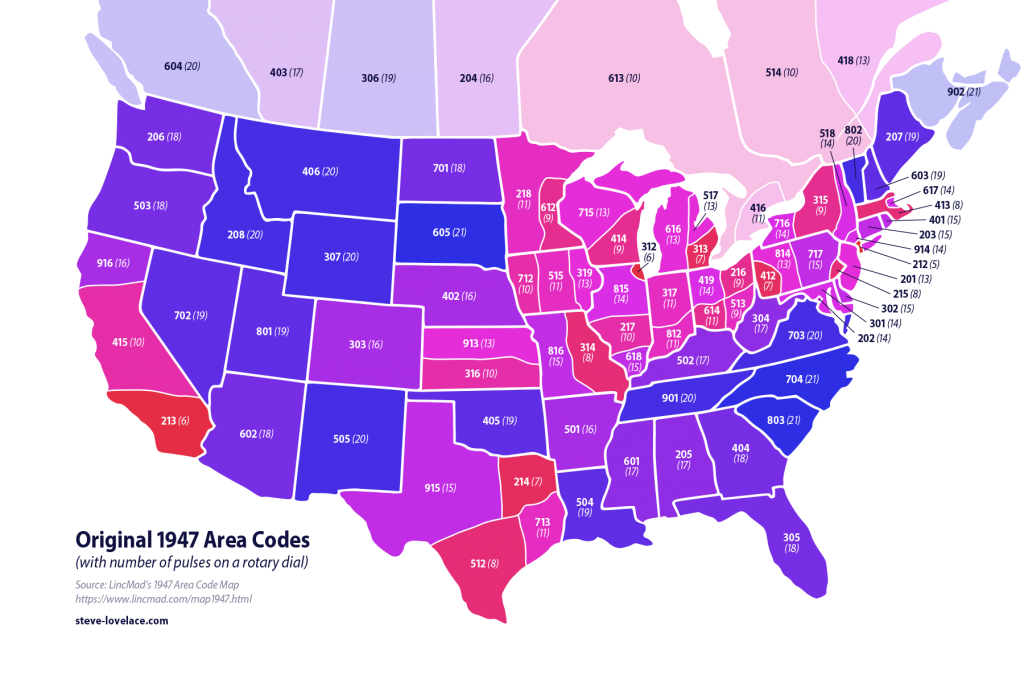

In 1947, the Bell System announced the North American Numbering Plan (NANP). This assigned area codes to the 48 US states (Alaska and Hawaii weren’t yet states) and the nine Canadian provinces (Newfoundland wasn’t yet a province.) Phones of this era were rotary only, with the numbers arranged on a mechanical dial. Each number from 1 to 9 would momentarily break the circuit (pulse) one to nine times, with 0 pulsing ten times. With this system, it took quite a bit longer to dial 909 (28 pulses) than it did to dial 212 (5 pulses). So engineers being engineers, the creators of the NANP arranged the area codes so that more populous areas would have less pulses.

Population vs Pulses

Area codes with a “1” in the middle were more desirable than those with “0” in the middle, since they were nine pulses shorter, saving the caller nine-tenths of a second for every call. So the NANP plan allocated “1” area codes to populous states/provinces with multiple area codes, and “0” codes to less-populated states/provinces with only one area code. Within each of these two categories, areas with bigger populations got smaller numbers. New York City got 212, the only area code with just five pulses. Los Angeles and Chicago got the second-best area codes, 213 and 312. Meanwhile less populous areas like South Dakota and Canada’s Maritime Provinces got area codes with 21 pulses. However, the area code assignments do not correspond one-to-one to 1947 population figures. The engineers at Bell Labs, it seems, had some leeway in assigning the numbers

An Expanding System

From 1947 to 1990, the number of area codes grew at a steady pace. A number of tweaks were made throughout the 1950s, adding area codes for places like Fort Worth, Long Island, and northeastern Indiana. As early as 1954, the pattern was broken, with new “0” area codes being assigned to states with multiple area codes. The system was later expanded to include Mexico and several Caribbean nations, though Mexico left the system in 1980. By that time, the number of “pulses” in the numbers didn’t matter so much, as the phone system slowly switched over to touch-tone dialing. By the early 1990s, the North American Numbering Plan seemed to have reached a stable plateau. Then all hell broke loose.

Cell Phones, Fax Machines and Deregulation

In the early 1990s a confluence of changes brought the NANP to its knees. Population shifts created a host of new major cities in places that previously had only one or two area codes. Then came things like fax machines, dialup modems and the now-ubiquitous mobile phone. This drastically increased the need for new numbers, but the biggest factor was deregulation. Ma Bell broke up in the 1980s, and now there were competing phone companies. Each company was given phone numbers in blocks of 10,000, a holdover from old mechanical exchange offices. This meant a startup telephone company could “use up” thousands of numbers without ever serving a single customer. With all of this in place, the old x0x / x1x codes weren’t going to work anymore.

New Area Codes

Quickly running out of numbers, the NANP started allocating area codes without a 0 or 1 in the middle. By this point, most telephone switching systems were digital, so they could simply be reprogrammed for new types of area codes. Dialing a “1” before a ten-digit number told the real-time landline system to expect ten digits instead of seven. And with cell phones taking over, it wasn’t as big of an issue as it was in 1947. What was a big issue, however, was constantly changing people’s phone numbers. Ever since 1947, the NANP plan created new area codes by splitting existing ones. This was a fairly simple procedure for the phone company, but it caused havoc for local homes and businesses, as millions of people were forced to change their phone numbers.

Splits vs Overlays

To see how chaotic the whole system has gotten, let’s take a look at Dallas‘ area code 214. One of the original NANP numbers, 214 was split early in its history, with Fort Worth’s 817 area code being created from 214 and neighboring 915. After that, it was stable for the next 35 years, covering Texas from Dallas to Texarkana. In 1990, the East Texas portion was split off into 903, but within five years, 214 was running out of numbers again. In 1995, area code 972 was created for the Dallas suburbs, with millions of people changing their phone numbers. Just two years later, they ran out of numbers again. To keep from changing everyone’s numbers again, Dallas got an overlay. Area codes 214, 972 and 469 would cover the entire Dallas area, and residents would have to dial 10 digits for every call.

The Future of Phone Numbers

The crazy expansion of area codes has slowed, though it certainly hasn’t stopped. Allocating new numbers in blocks smaller than 10,000 has led to less “wasted” phone numbers, and modems and fax machines are on their way out for the most part. But still, the number of numbers continues to grow. A 2014 study estimated that we will run out of numbers by 2044. By then, phone numbers will have to expand to 12 digits, with 214-555-1212 becoming 2140-0555-1212. These 12 digit phone numbers are hard to visualize and hard to remember, but since we program numbers into our phones anyway nowadays, I don’t anticipate it being an issue. The future of area codes, and phone numbers in general, will be as invisible connections, like the IP addresses behind every website. Phone numbers aren’t going away, but we’ll see a lot less of them in the coming years.

What do you think about area codes in North America? Let me know your thoughts in the comment section.

Very interesting. I remember the old “Ma Bell.” I predict four digit area codes will be here by 2025 – latest.

In Brazil, areas codes are set up in a geographical order.

As a retired telco (Verizon) technician, I find this information quite interesting. Over my working years, I was given a lot of training, but this subject was never covered. Thank you for your explanation.

Lots of good info here. I was told the same story about pulse counts correlating with population, which is true for the first 3 largest cities at the time. But that story is incorrect, according to the experts of the Telephone Collectors International. For example, the entire state of FL, including Miami, had the 18-pulse code “305”, while southern KA, including Wichita had the 10-pulse code “316”. (A state like KA was split because of technical issues associated with physical long distance switching and transmission hardware, not due to a large volume of phone numbers.)

The main “rule” in original NANP code assignments was this: States and provinces covered by a single NANP code always have a “0” as the second digit. For example, MT and NV. States split over multiple NANP codes always have a “1” as the second digit in each code. For example, CA and NY. This was a signal to long distance operators who still placed many calls during the transition. Actually, LD operators were using the NANP codes even before they could be used from user phones. Of course, all the most populous states needed to be split, and those split state NANP codes included most of the largest cities. Thus the misimpression.