Media and Writing Systems

I’ve noticed that writing systems are affected by the media on which they are written. This explains a lot from the shape of specific fonts to the form of entire writing systems. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

I’ve noticed that writing systems are affected by the media on which they are written. This explains a lot from the shape of specific fonts to the form of entire writing systems. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Chinese

A good example is the Chinese writing system (as well as Japanese kana). Chinese is traditionally written with a brush instead of a pen. This leads to characters that flare at one end of each stroke. It also means that stroke order is important, regardless of the writing instrument. Most importantly, it helped evolve the characters from simple pictograms to more abstract characters that represent morphemes and abstract concepts. This in turn allowed the logograms to survive and thrive in the modern world.

Arabic

Another example is Arabic script. Arabic evolved from the same Phoenician alphabet that gave us Hebrew, Greek, Cyrillic and Latin, but unlike these other writing systems, Arabic is cursive by default. Arabic characters are usually connected, and each letter has several forms depending on its placement. Why? Because Arabic evolved from a strong Koranic tradition. In the early Middle Ages, Islam spread quickly across the Near East. Since there were no printing presses, there were a lot of Korans being copied. In addition, Islam’s strict prohibition on idolatry put more an an emphasis on calligraphy. The result is a fluent flowing script that survives into the information age.

Latin

Stone Inscriptions

When it comes to the influence of media on writing systems, our own Latin alphabet is one of the most fascinating instances around. While derived from the Greek Alphabet, the Latin alphabet is a lot curvier. While both the Greeks and the Romans carved letters into stone, the Romans had a tendency to paint the letters on with a brush first. Thus the square-bracketed gamma (Γ) evolved into the round C and G while the zigzag letter sigma (Σ) evolved into our curvy letter S. Then there are the serifs, those little hooks on the end of so many letters. They also come from Roman inscriptions. Whereas the serifs on Chinese characters come from brush strokes, serifs on Western characters come from chisel marks. You can still see the shape of an ancient chisel in modern-day fonts like Times New Roman

Medieval Monks

A lot has changed since the Romans built their monuments. One of the biggest changes has been the invention of lowercase letters. Not every writing system has them. In fact, lowercase letters are confined mostly to writing systems that come from Christian countries originally: Latin, Greek, Cyrillic and Armenian. To understand this phenomenon, we have to go back to the Middle Ages. The Romans used letters mostly for big monuments, but in the Middle Ages, writing was confined mostly to monasteries. For centuries, almost all Western writing was done by monks copying Bible verses. Over time the letters adapted to new forms. They became rounder. They went above and below the baseline so they didn’t all line up. After a thousand years of pen-and-ink copying, they evolved completely new shapes. Then came the Renaissance.

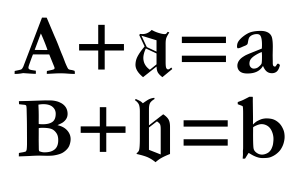

Lowercase

The ancient Roman version of the alphabet wasn’t forgotten. In fact it was highly esteemed, more so than the minuscule letters of the Middle Ages. The large monumental letters were used for important things like names and the first letter on a page. But they were still two separate alphabets, or at least two separate styles of writing. This all changed with the invention of the printing press. For a while printing presses mimicked the form of handwritten lettering, until an early Italian printer named Aldus Manutius had an idea. He took the small handwritten shapes of medieval manuscripts and made them match the ancient Roman letters. He gave them the same kind of chisel pointed serifs that the uppercase letters had. Just like that, he combined the medieval and classical letters into the modern alphabet.

Sans Serif

Interestingly enough, sans serif fonts like Helvetica, with their unadorned forms, are much newer. They didn’t come into being until the 19th century, when mechanization allowed printers to cast more simple geometric forms. That brings us today, where letters are stored mathematically as algorithms to be used on computer screens whenever necessary. And even though the information age opens us up to a world of new and exciting fonts, the media still has an influence over the shape of the letters. Fonts like Tahoma and Verdana are designed to be read on computer screens. Who knows what our writing systems will look like in a thousand years? Whatever happens, I’m sure it will be interesting.

3 Responses

[…] Greek Alphabet was adapted from the Phoenician writing system. This was less than ideal, since Phoenician was a Semitic language with a very different sound […]

[…] ago I read that Arabic and Hebrew and other right-to-left writing systems still write their numbers the sane way we do, with the highest-valued digit first. At first I […]

[…] every other. Comic Sans was designed back in the days of ASCII, when a font consisted of the basic alphabet and numbers (and maybe a few basic “foreign” characters.) Nowadays we have OpenType […]